Ghost Colonialism

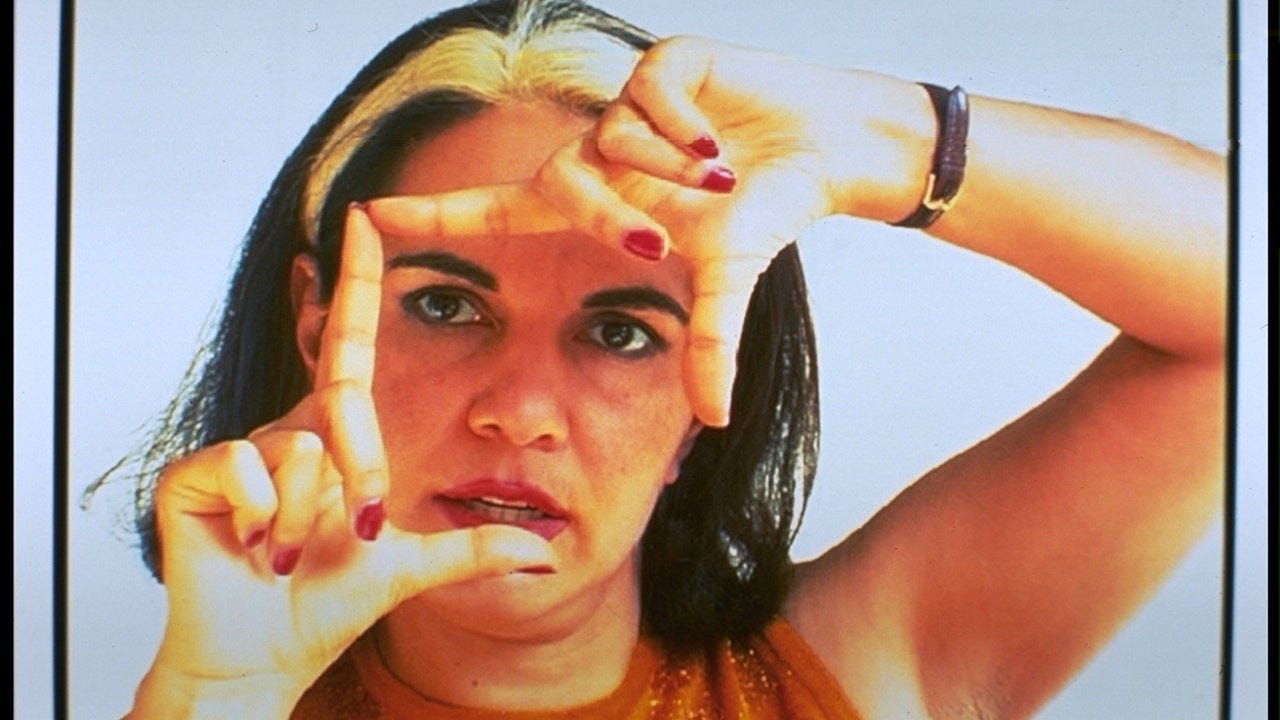

The Radical, Magical Films of Tracey Moffatt

It is a testament to the insularity and cultural chauvinism of the United States that in this country, the work of the Australian multidisciplinary visual artist and filmmaker Tracey Moffatt is not more widely known, screened, or exhibited. For the first couple decades of her career, which kicked off in the 1980s after she graduated from the Queensland College of Art with a degree in visual communications, that may have been sadly understandable. Moffatt is half Aboriginal and female, her work is boldly experimental yet often playful, and in turns ironic and grotesque—it ranges across photography, filmmaking, performance art, and traditional visual art, and finally, most forcefully, Moffatt often reckons with the ugly history of Australia’s colonial past as it returns to haunt the present. That is to say, Moffatt is a challenging, uncompromising, hard to categorize artist whose work is even harder to confront if you cling to any of the foundational, epistemological myths that were once used to justify the exploitation of the so-called “fourth world” of the indigenous global south.

But in our contemporary moment, where Black abolitionists have ushered in a worldwide movement against the hegemony of white supremacy, where indigenous land and water protectors have fought and died to stymie the carnivorous growth of capitalism, and where it seems a new dawn of opportunity has broken upon radical indigenous, aboriginal, and refugee artists, there remains no excuse not to exalt Moffatt as a central force in the creative contingent of the movement to liberate all lives from bondage. To be more direct: there is no reason not to call Tracey Moffatt exactly what she is—one of the most prescient and powerful living artists in the world. Perhaps key to the disparity between the quality of Moffatt’s work and its relative obscurity, at least in the States, is its complex, layered nature. Moffatt makes films that read like highly staged, non-narrative performance art, and photographs that have the tactile, turbulent quality of film. She uses humor to reveal horror, autobiography to tell communal history, and artifice to extract the cold, hard truth. Lack of interest is a certainly a part of the problem. But lack of understanding may be part of it too, and that can be more readily addressed.

I want to develop a strategy for engaging with Moffatt’s work, in hopes that others can discover the pleasures that lie locked inside her tricky, tough to crack aesthetic and narrative forms. As a modern, multicultural woman who was born to an Aboriginal mother and raised by an Irish-Australian foster mother, Moffatt understands that there’s no way of representing the “truth” of Australia by saying it straight. Only a highly braided, layered, and hybridized approach that defies easy categorization can speak across racial, gender, and class lines to encompass the whole of the continent, fractured as it was by colonization, family separation, and genocide. In her films in particular, and my focus here is mainly on Nice Coloured Girls (1987), Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy (1989), and beDevil (1993), Moffatt targets the anthropological, taxonomic binaries that the British imperial project sought, and failed, to compress aboriginal Australian culture into. Through her layering of fact, fantasy, past, present, sound, color, and movement, Moffatt frees the viewer from the cognitive shackles that colonialism’s binaristic ordering system has forced us all into.

I’ll focus on four main oppositions that recur across these works: the past/the present, official secrets/personal histories, documentary/fantasy, and real locations/studio sets. Through her sometimes playful, sometimes horrific deconstruction of these binaries, Moffatt restores female aboriginal existence to the splendor of its full complexity, and thereby shows that representation and art-making are crucial tools in the ongoing struggle to uproot the destructive legacies of colonialism from countries and communities across the global south.

'40,000 years of dreaming, 200 years of nightmares’: The Past and The Present

In her exhaustive chronicle of Australian Aboriginal history, the writer and historian Jennifer Isaacs recorded a popular Aboriginal aphorism that succinctly captures a view of Australia’s modern history that is rarely aired: “40,000 years of dreaming, 200 years of nightmares.” There is no way to understate the impact the British empire had on the islands of Australia, New Zealand, and Tasmania when they began exporting convicts to form penal colonies there in 1788. By the time the commonwealth officially claimed the continent within their legal and economic dominion in 1829, just under half a century later, life for the people who came before—who had always called these lands their home—had changed forever. And for the worse. Sue Ballyn describes the catastrophic, far-reaching effects thusly:

“Indigenous peoples were to find themselves exiled from their homeland and embroiled in a cultural dislocation, brought about by British and colonial intervention against their peoples, the evidence of which remains only too strongly with us today. Genocide went hand in hand with the policy of eugenics which in turn led to the forced removal of half-caste children from their families, bringing about an exile upon exile. Indigenous peoples were exiled from their lands and taken into missions and then their children, often the product of rape, though also of long/short standing relationships with the white man, were dragged away from their mothers and taken thousands of miles away to be “educated,” thereby becoming doubly exiled from their familial roots.”

Half Aboriginal by birth and raised between two traditions, Tracey Moffatt refuses in her work to capitulate to the myth that “what’s past is passed.” If Aboriginals want to get on equal footing with white Australians, so the settler logic of bootstrap individualism goes, they should focus on the opportunities of the present, not dwell on the setbacks of the past. Moffatt’s films expose the calculated naïveté and sinister austerity of that logic by collapsing the distinction between the past and the present, or as Cynthia Baron writes, “establish[ing] connections between personal ghost stories and national nightmares.”

In the short for which she first received widespread acclaim, 1987’s Nice Coloured Girls, Moffatt utilizes experimental filmic strategies such as voiceover, double exposure, the fourth-wall breaking gaze, and the insertion of non-narrative vignettes into a traditional narrative flow to show the every day recurrence of the colonial past in the Aboriginal present. In the opening sequence, three young Aboriginal women walk down the street, laughing a great deal, secure in their camaraderie. They’re each dressed in highly personalized ways, and their distinct, carefully coiffured hairstyles suggest the work of thoroughly modern, self-possessed individuals. Yet a male voiceover begins to play over the image, countervailing what we see with what shortly is recognize as the distorted, regressive voice of the past: “If ever they come near you, they appear as coy, shy and timorous as a maid on her wedding night. But when they are as they think out of your reach they holler and chatter to you, frisk and flirt and play 100 wanton pranks.” These are lines from real travel diaries kept by explorers as they made first passes around the islands in the late 18th century. The mental image of the first generation of Aboriginal women to confront white settlers, characterized as shy, playful, and curious is confronted by a real image of Aboriginal women, wholly unconcerned with the white gaze.

Moffatt pushes it even further by following the girls into a bar in the raucous King’s Cross neighborhood where they allow a drunk “captain” to court them. “We call them captains because that’s what our mothers and grandmothers called them” reads a subtitle, which stands in for the girls’ speech—another callback to the era of the invaders. The gaze of the camera is completely aligned with the sober young women, sickened by the repulsive display of the slobbering, old white captain. He sloshes his drink around, and his eyes loll around with it, closing and opening like a stunned child. He opens himself up to be completely swindled by the girls, who steal his cash and eat off his dime. “Most of the time we’ve never got any money, so we pick up a captain and make them pay for our good time,” reads another subtitle, and Moffatt lays down one more complicating, time-bending layer—a cut to a shot of an older Aboriginal woman in traditional, pre-colonial dress staring directly into the camera. She nods and giggles as if in direct conversation with the girls, approving of their cunning reversal of the exploitative relationship set up by colonialism, in which indigenous populations are only ever extracted from. It’s more than just the contemporary image of Aboriginal women that Moffatt reclaims in Nice Colored Girls. The veracity of historical accounts of the “comely,” “timorous maids” of the islands is called into question through the collapsing of the present into the past, and their mutual re-contextualization of one another.

Official Secrets and Personal Histories

Moffatt does more than merely intertwine the present and the past to dismantle the notion that no trace of Australia’s history of brutality and bold-faced racism continues to linger on today. She further utilizes the autobiographical form, deploying her own personal history to expose the “official secrets” that were strategically implemented by the Crown to enshrine that brutality and that racism as the law of the land.

“Every art piece I have ever made, be it film or photographs, is in some way autobiographical,” Tracey Moffatt said in an interview for a 2003 retrospective of her work at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney. Moffatt’s 1989 short film Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy is one of her most nakedly personal works as an artist. It is also, in its abstract, poetic way, the most politically searing. In it, a middle aged Aboriginal woman (played by the Aboriginal scholar Marcia Langdon) cares for her ailing white mother (Elizabeth Gentle) in a shack in the middle of a surreal, vividly colored studio set meant to “locate the story within the glare and heat of inland Australia and establish the film’s story as one of human endurance,” as Summerhayes puts it. And endure our protagonist does, for better or worse. Moffatt herself was raised in a state of cultural dislocation, given over by her Aboriginal birth mother along with three siblings to a white foster mother who already had five children. She paints the piercing emotion of that experience onto its resonance in broader Australian history: the “Stolen Generation” of Aboriginal children forcibly separated from their parents and placed in white foster homes. This official policy, which was in effect from the 1900s to the late 1960s, has been called a “cultural genocide” by Aboriginal scholars and human rights commissions around the world. But throughout its active phase and long after, even up to the present, the government has downplayed the scope, and suppressed the broader implications this policy had on Aboriginal communities.

In Night Cries, Langdon’s winsome daughter alternately resents her adoptive mother, angrily cutting up her food and spoon-feeding it to her when she’s too weak to do it herself, slips into bitter reverie of memories of seaside trips where her mother played her own abandonment act on the kids, and finally, most painfully, curls up and cries at her side as she dies. Moffatt layers the complex matrix of torturous emotions generated by this kind of upbringing with exaggerated sound and visual effects to generate a real well of sympathy for the thousands of children who endured similar experiences. With that empathetic identification in the palm of her hand, Moffatt cracks open the hard shell of suppression that the Australian government, and the simple passing of time, have enclosed around that history. “Through her telling of ‘secrets,’” writes Catherine Summerhayes, “Moffatt continues to break through the official discourse about indigenous people in Australia that has been carefully controlled by the institutions of academia, religion, the state, and the art industry.”

“An Effect of the Real”: Fantasy and Documentary

In the introduction to an interview the artist Coco Fusco conducted with Moffatt for BOMB Magazine in 1998, at the height of Moffatt’s fame as an international art star, Fusco remarked that “Moffatt creates images in real settings with “real people,” but the combination of artful composition and elusive referencing of cinema reconfigure that realism as an ‘effect of the real.’” One of the more vertiginous methods by which Moffatt bewilders the operating logic of colonialism, and thus breaks up its binaries, is by phasing together the documentary mode with fantastical stagings of exaggerated artifice. Moffatt does not muddle the distinction between fact and fiction for dramatic effect, or as an aesthetic end to itself, but because the history of representations of the Aboriginal people has been marred by deception, distortion, and schadenfreude. White male power centers, which have long held a monopoly on image-making technology, have manipulated the image of Aboriginees and telegraphed it back to the imperial core as “truth.” Moffatt wields her own cinematographic weapons of fabulism to shake up official “truths,” and brings an ancestral history of inherited truths to bear on historical chain of lies.

Moffatt’s lone feature length film, 1993’s beDevil, utilizes several strategies to break down “truth” to get to truth. As Summerhayes has noted, Moffatt’s “explicit use of direct address and ‘fake interviews’ calls attention to both the quantity and quality of discourses from anthropology and ethnographic filmmaking.” beDevil is collection three shorter films whose narratives are distinct, but have much in the way of thematic and formal overlap. In the first two—“Mr. Chuck,” about a the ghost of a WWII G.I. who haunts a swamp on Birbie Island, and “Choo Choo Choo Choo,” about the ghost of a little white girl who haunts a decommissioned strip of train tracks that an Aboriginal family lives next to in the outback—Moffatt employs what she calls “documentary characters.” These characters are actors who play “real people” providing testimony in verite, direct to camera addresses. These segments are edited into and around highly staged, dramatic recreations of the events being discussed, which frequently shifts between modes of the comic, the supernatural, and the horrific.

Moffatt decouples the conventions of documentary filmmaking from the ascertainment of truth. Once those conventions are disembodied, she appropriates and fuses them with the fantastical—Brechtian performances of “authenticity” collide with mundane portrayals of incomprehensible horror. The mixture of the “gritty realist” and dreamscape fabulist modes challenges the dehumanizing, ethnographic portraits of Aboriginees that have shaped their public perception by restoring to them all that was missing of their humanity—the mirth of laughter, the wonder of spirituality, and the dignity of sensuality.

“Our island home”: Sets and Settings

Finally, Moffatt’s films release the humanity back to all those yoked to the dehumanizing binarism of the colonial project by hijacking one small, but consequential binary: “real” places, or, location shoots—and “imagined” places, or studio sets. By revealing the supernatural and paranormal in natural, normal locations around Australia like Birbie Island, King’s Cross, and the town of Charleville, and conversely finding more vivid, comprehensible ways of picturing these locations by recreating them on sound stages, Moffatt recaptures the image making, and therefore meaning making apparatus from the colonial establishment.

The most spectacular example of a recreated location speaking more vividly to its corollary’s real dimensions than a photograph or documentary could in Moffatt’s filmography is the set of Night Cries. Moffatt constructed two primary locations for this film: the little shack, strewn with apple cores, empty cups, travel brochures, and flyaway shreds of newspapers, bathed in glaring orange light in the day, and somber blue at night, and the outback outside, a standing toilet encased in corrugated tin at the end of a rock-lined path—in the background, the deep brown outlines of mountain peaks cut a jagged line against a brilliant Australian sunset sky, orange, marigold, peacock blue and pink all streaked across the frame of each shot. In the absence of dialogue, or any coherent, linear, narrative momentum, Night Cries’ “audioviosual story … relies on vivid, glossy colors for its narrative power.” The impression of this region in Australia, the “no man’s land” that settlers would rather build railways to get through (see the haunted tracks of beDevil’s “Choo Choo Choo Choo” segment, or the moment in beDevil where the protagonist is pulled into a painful, fragmented memory of waiting in vain for a train at a stop) but never settle down to build a life in, is unbearably vivid. Using only visuals and dispensing with realist conventions of scene setting, Moffatt demonstrates how much more there is to our relationship to the land than what we can get from it. Her non-logical, non-linear, kaleidoscopic vision of the outback emphasizes the “profound distinction,” as Baron puts it, “between colonists and tourists romanticized views of the Australian landscape, and first Australians experience of subjugation and despair in seeing outsiders waste the land that had sustained aboriginal people since 80,000 BC.”

Just a few years later, in beDevil, Moffatt would push this experimentation with place to a boiling point, mixing real, staged, and half-altered locations to hallucinogenic effect. In “Mr. Chuck,” a composed, well-dressed white woman and a fidgety, mentally disturbed aboriginal man trade off sharing their recollections of the segment’s setting, Birbie Island. For the woman, “our island home” is visualized via soft-focus, faraway aerial footage of the tourist-dotted coastline, tinted at the edges and glowing at the center like a promotional video. But for the man, whose name is Rick, the picture isn’t so pretty. “I’ve always hated that place,” he grumbles. “That island,” he says with contempt. Rick’s childhood memories of Birbie Island are full of hunger, poverty, and abuse, and are represent in immaculate detail and at startling expense in a studio, where a bubbling swamp surrounded by reeds, crossed by a flimsy plank of wood and crawling with fog has been built. Pleasurable memories cannot be extricated from Rick’s painful memories of the land (Rick experiences real trauma at that swamp when the G.I. ghost grabs his foot; he also pads around it with his siblings as intimately as if it were his home). His Birbie Island is constructed in hyperreal detail, blossoming with vivid sensory detail, where the white woman, despite her fondness for the place, is continually shot from outside her home, encased within the large living room windowpane like a jail cell, palms flat on the surface, a frown pulled down at both corners of her mouth.

Rick’s raw connection to the land supersedes the limits inherent to the camera when trained on nature; his Birbie Island must be constructed on a set. The white woman’s artificial connection to her “island home,” however needs no production design. Her barren, isolated home speaks volumes of her relationship with the land. This strategy of heightening the natural and naturalizing the heightened dislodges the real, lived-in locations that Aboriginal communities have lived in and derived meaning from for millennia. Films like beDevil can help all Australians, not just Aboriginal Australians, wake up from the “200 year nightmare” and re-encoutner a land untouched by greed, exploitation, and malefaction.

Conclusion

The films of Tracey Moffatt are bewitching, bedeviling things to behold. They appear at first to the viewer as quirky, canny, flights of fancy, full of tittering soundscapes and luscious landscapes. But from the edges, a disquieting horror begins to seep. Light flickers and fails, heightened performances suddenly crash into grave, somnambulistic meditations. Most befuddlingly, the viewer’s original perception of humor and whimsy is not displaced by the later darkness, only added to. Baron writes that Moffatt’s “films contain dense structures that insure that nuances and images central to the poetic text are illustrated many times over, until the layers of expression render metaphors that are both apt and enduringly memorable” (161). In fact, Moffatt’s methods have broader implications: as a multicultural, modern Australian, an Aboriginal woman with heritage on both sides of the colonial divide, the only way for Moffatt to speak directly and meaningfully across difference is to speak in a collective voice. Only by utilizing the cinematic strategies of layering, repetition, and fusion is Moffatt able to break through the resilient binaries that the Imperial project forced Aboriginal culture into and tap into that collective voice. With it, she has spoken some of the most poignant films that we have into existence.

…

Notes

Sue Ballyn, “The British Invasion of Australia. Convicts: Exile and Dislocation.” Lives in Migration: Rupture and Continuity. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona Press, 2011.

Cynthia Baron, “Films by Tracey Moffatt: Reclaiming First Australians’ Rights, Celebrating Women’s Rites.” Women’s Studies Quarterly 30:1/2 (Spring/Summer 2002): 151-177.

Coco Fusco, “Interview with Tracey Moffatt.” BOMB Magazine. July 1, 1998. https:// bombmagazine.org/articles/tracey-moffatt/

Bob Hodge and Vijay Mishra, Dark Side of the Dream: Australian Literature and the Postcolonial Mind. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1991.

Jennifer Isaacs, Australian Dreaming : 40000 Years of Aboriginal History. Sydney: New Holland Publishing Australia Pty. Ltd., 2005.

Tracey Moffatt, beDevil. Women Make Movies, 1993.

—, Nice Coloured Girls. Women Make Movies, 1987.

—, Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy. Women Make Movies, 1989.

Catherine Summerhayes, “Haunting Secrets: Tracey Moffatt’s beDevil.” Film Quarterly 58:1 (2004): 14-24.

“Tracey Talks.” Edited by Elizabeth Ann Macgregor. Sydney: Museum of Contemporary Art, December 2003 – February 2004. Exhibition catalogue, https://www.austlit.edu.au/austlit/page/7305910.

van Krieken, Robert. “Rethinking Cultural Genocide: Aboriginal Child Removal and Settler- Colonial State Formation.” Oceania 75:2 (Dec. 2004). 125-151.