The Ends of the Affair

Conflict between the surface and the depths of 'Halloween Ends'

It’s cliche and often condescending to say that there is a better or more interesting film inside a film you found bad or dull. In the case of Halloween Ends - the final, my god, AT LAST!, gratefully the final film in David Gordon Green’s miserable, mixed-up trilogy of reboots, this description is also inaccurate. There isn't a better film inside Halloween Ends, but beneath it. Splayed out across the surface of this film is the same bleak and degraded landscape of the previous installments. A charred-out, desiccated terrain that haunted figures who look like people rove through, and big, crude, numb, empty blocks of concrete and wood jut into the air, appearing to the naked eye as the charming houses and businesses of a small American town but registering immediately inside the intuition, within the realm of the special senses with which we really experience cinema, as the intimations of a broken man's broken vision of the world. Though these films are no darker (visually, not thematically) or more disorientingly shot in their bland compositions and countless, needlessly microscopic super-closeups than your average contemporary horror film, but to recall them is to call back voids of light and color, smeary, charcoal-dark images of wounded people, their mouths distended open in panic and agony, no eyes, just gaping mouths shouting into a bombed out ruins.

The thing that sucks about David Gordon Green's Halloween movies is that his unremittingly tragic view of life is also dull, virginal, moralistic, and conservative in its fearful reluctance to give itself over to the animal brained, psychosexual logic of the slasher -- the most Freudian, internally divided, and death-driven of all horror types. Next to a film like 1974 Black Christmas, DGG's Halloween movies look like Netflix documentaries, which is to say the most didactic and least groovy among all types of contemporary cinema. And also stupid.

And yet it is on this point that Halloween Ends surprised me. Bind me to the scaffold and beat me if you wish, but I sense something deep within this film that, like an ancient talisman accidentally disturbed by a clumsy passing fish or the falling baleen tusks of a whale, which blinks to life and signals to an oracle or triggers a volcanic eruption, there is something beyond what words can easily describe about this film, eclipsed by the numb splatter of gore and exhausting IP maintenance, that nonetheless gives it a charge unlike anything I've felt in a slasher in years. It isn't Black Christmas, it isn't Candyman or Carrie or Orphan but it's as if one of those films was eaten and only partially digested by Halloween Kills, which is probably in the 10 worst horror movies of the new millennium for me. But there’s an intricate pattern lodged deep within this film that specifically has to do with the characters, kind of like scrawlings on the ledger of its unconsciousness that are tautly charged and even powerful.

I talked to a couple people when Halloween Kills came out who shrugged off every complaint about it that I threw at them. Not because it had a vibe they liked or that it did something particularly interesting as a counterbalance, but because technically it wasn't bad. It wasn't good either, but in its middling, mind-numbing, narrative flip-flopping, never-ending midness it almost wore on them, like a dull pain that you grow used to. You wouldn't miss it if it stopped, but it kind of reminds you you're alive and can induce a strange sedative effect, pain like that having a kind of libidinal torpor (remember how you felt when you watched the tooth sanding scene in The Handmaiden). If Halloween Ends was a broad yet shallow pool of water that could convince you your endless churning of water just to stay conscious was actually an edifying swim toward meaning, Halloween Ends is a deep lake. It's deep (just bear with me through this), unfathomably so, though not in the way you’d call a wise person deep or an enigmatic Bergmanesque movie deep. Not every stratum of water here adds to the general richness of the film, Halloween Ends is deep in the sense that whatever neurons are wired together in the right circuit pattern are arranged thus so far beneath the consciousness of the film that they affect it in subtle ways, but effect it they do.

This has to do with character, because good slashers (I don’t think just the ones I like, really all the good ones), gather their electric force from the dialectical circuitry of domination and submission between the characters. And not just domination and submission, other charged oppositions too — innocence and corruption, abandon and refusal, of course masculinity and femininity. And there are other, more convoluted matrixes whose irreconcilable stakes in the film can generate a lot of tension and feeling. There is the ricocheting around and around between sex, death, and rebirth (or renewal, symbolic baptism), and between affective states like ecstasy, rage, and dark humor. But slashers primarily work on the polarities of sex and death, and masculinity and feminity.

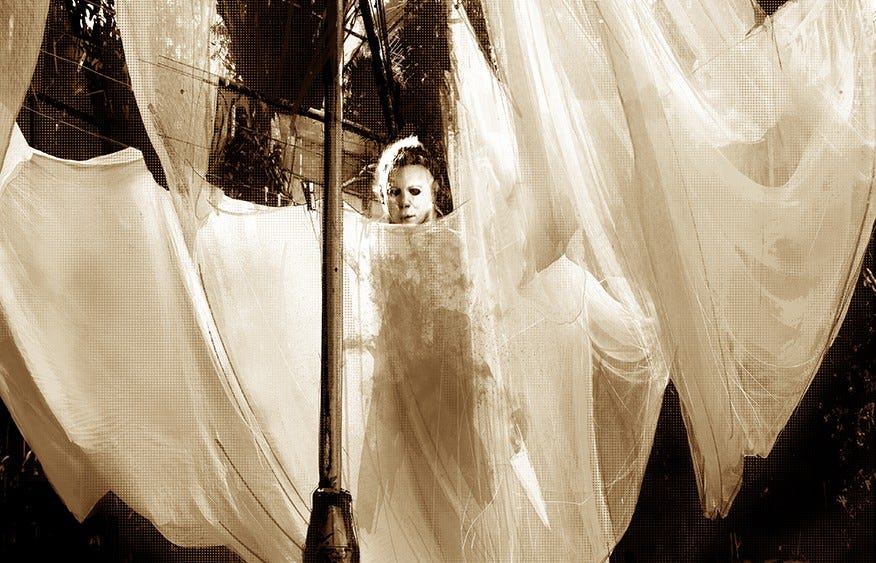

As Carol Clover so indelibly pointed out in Men, Women, and Chainsaws, the gender dynamics in the most effective slashers are imbalanced to an unsettling degree. Halloween is as good an example as Black Christmas, with its primal scream of eternal misogyny that comes leaking out of the receiver whenever the phone is picked up, or in (instructively) crude gialli like The Whip and the Body or Tenebre, or anything starry Mimsy Farmer, whose stylization and staginess overwhelm attempts to analyze them, making the interpretation richer for the interpreter’s having to resort to the instinct and not intellect. Michael Myers is genderless — The Shape — in his baggy workman’s coveralls and his androgynous mask that looks as much like Glenda Jackson as it does William Shatner, whom the mask was apparently meant to resemble before the original production team bought and anonymized it. He ever wields his phallus — his massive, glinting, rock-hard butcher’s knife, comically large like a cleaver, and floats towards his victims unhurried, like a fog.

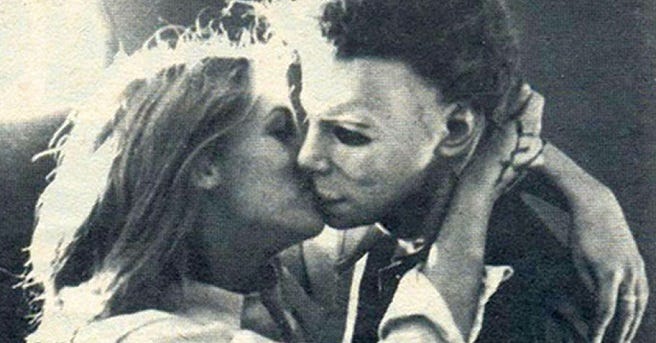

One of my biggest pet peeves with the DGG Halloweens is Michael being suped up like a jock slasher who runs, jumps, punches, kicks, and thrashes. The contrast of 1978 Michael’s elegant, eerie slowness and the steadiness and his ice-cold, unquenchable thirst for blood not only made him an interesting figure but a mixed one when it came to gender. He “entered” his victims, but never aggressively. He phased into them, rather than ripped and tore into them. While I see Michael as distinct gender-wise from slashers like Leatherface (inbred, constant visual allusions to deformed genitals) and Jason (actually a woman in the first film), Clover would say they all share in a “compromised” masculinity. And Laurie’s “compromised” femininity is even plainer to see. From the first moment you see her in Halloween it’s clear she’s not like other girls, and not in a twee or cute kind of way, in the way that Jamie Lee Curtis has simply never exuded anything close to what women in horror, and particularly women in slashers tend to exude (which constitutes them as female, and not the other way around) — vulnerability, softness, desirability. Clover writes that it’s the final girl’s recusal from the sexual world which allows her to “gaze,” and it’s this rare penetrating woman’s gaze which lures the phallic killer out of the shadows. But it seems to me more that Laurie and Michael’s aberrations are what draw them to each other, link them together, as illustrated a bit literally, but to me, powerfully in the Halloween Ends finale in which Laurie and Michael hold hands as he bleeds out, actually dying this time.

What makes Halloween Ends compelling to me is the grid that is formed between Laurie, her pursuer, Michael, his protegee, Corey, and his girlfriend, Allyson, Laurie’s granddaughter. Honestly, I was totally compelled by this character arrangement, regardless of the often clunky, forced, and tedious movie that was happening all around it. Within this nexus, violence, protection, revenge, and sacrifice form links in blood, and beneath that, even deeper states are activated — sanity broken by willful, malicious ignorance, the violence of scapegoating, unyielding trauma which creates an agitated and unhealing spiritual wound, the masculine urge to kill, the feminine urge to be killed — when Laurie has both Michael’s arms and one of his legs pinned down and has slashed his throat, he lets the knife rip through one of his hands and grabs her by the throat. “Do it,” she says. And she’s said it before, in many prior movies, and especially these three, but this is the only time I really felt she meant it. It would have made as much sense for Michael and Laurie to die together as for Allyson and Laurie to both survive.

Because this is where slashers ought to operate — in a rickety lean-to hastily erected over the beating heart of the sex/death exchange. Feminist film theorists like Barbara Creed and Teresa de Lauretis have written hundreds of pages on this primeval well which spews up so much energy, which has been the primary site from which horror artisans like Tobe Hooper, Mario Bava, and Sion Sono have all drawn the power and organizing principles for their films, and not just the slashers. But too frequently they focus on films where the dread logic really is causal, and thus, misogynistic — deformed freak wants to stab girls because he can’t fuck them. Certainly there are plenty of films that do tell this story, and a lot of them are good! But Clover got closer to the truth in Halloween, where the relationship between Michael and Laurie is rightly depicted as coeval, elliptical, mysterious. The drive toward death, and the shackles of gender deformity which unite them keep them both from dying, or more accurately, from fucking each other to death. I got chills when Laurie delivers the final blow against Michael in Halloween Ends, because she does it with a whimper, not with a bang. After punching each other, throwing each other around in the kitchen, mutual stabs, frying pan slams upside the head, etc, Laurie has Michael pinned to the island in her kitchen, like a frog about to be autopsied. After stabbing him deep in the side with a huge knife and slashing his throat, he still fights back, choking her, which brings her incredibly close to him. She is compelled to mirror him in his dying moments — “Do it,” she murmurs, as he bleeds out. If her granddaughter hadn’t run in and given her a Women’s Intergenerational Trauma assist, would Michael have spoken back? The closeness between the two in this moment felt unbearable to me, made all the more excruciating given the fragility of their mutual old age, which was depicted well in the preceding fight. They seemed to be occupying a delicate world together, their mutual bloodlust, fear and frenzy finally quenched in their dying moments, finally, both giving up the fight and embracing abandon. Yet Laurie is yanked back into the grim sobriety of DGG’s world. But when she actually kills Michael (nevermind the later scene when she dumps his body into those pulverizers you see on TikTok lol), she does so with a delicate slash across his wrist, longwise. Something about this gesture, the tenderness of its brutality, brought me back to the Freudian slasher of the ‘70s, so far from the hardboiled (and very stupid) intellectualism that is the dominant idiom of this trilogy, from all the handwringing and mouthpiecing and horrid “social commentary.” This is what slashers are about: man and woman, drawn together in the bloody embrace of a shared suicidal ecstasy.

If it sounds like I’m saying that slashers are better the more unconscious they are, let me assure you that I am. It is possible to make a good horror film whose aim is to be “smart,” whose primary language is the cerebral rather than the instinctual. Think of David Cronenberg, whose many “body horror” masterpieces are all driven by the intellectual rather than something more primitive. You have to think about it to get scared, as opposed to a film whose craft actually frightening, like Noroi: The Curse, or whose mood generates the horror, like the films of Kiyoshi Kurosawa. Etc. I don’t watch a lot of slashers, compared to my comfort subgenres, haunted houses, ghosts, possession stories (feminine forms), because slashers need to be hermaphroditic to be good, and it’s very hard to achieve the right balance. It’s also morally and spiritually difficult to allow yourself to be drawn that close to the primal stuff of life and death, the facts of flesh and the unconscious, and many simply don’t have the stuff to get there. And when a slasher isn’t good it’s just killing, which just makes me sad! Lame as that is.

I watched Halloween Ends less than 12 hours ago and the same corrosion of detail is already taking place in my mind. I can’t remember what most of the characters look like, all the locations are melting into the same condemned black site. But with the last two, what remained were fragments of the idiotic “ideas” that DGG was hurling at the audience like tomatoes. With Ends, what lingers for me is this memory of the primal scene, man and woman, and of the larger pattern that surrounds them. I applaud DGG and his 15 cowriters (Danny McBride? …. 😪) for finally doing what a reboot should do — say to hell with all the lore and narrative infrastructure and fan demands and create something uniquely psychically compelling. Unbelievably, introducing another new character who also had some shit happen to him on the wretched Halloween night 2019 that DGG cannot stop returning to ended up being a great idea. And the casting of Rohan Campbell was perfect; his sublime mixture of masculine and feminine traits — his pillowy, plumped-up lips and his fleshy, glowering brow, his cartoonish Ron Pearlman chin and delicate, close-curling hair, his fluttering lids, eyes downcast and alternating between vulnerability and rage. He closes a circle between Laurie, Michael, Allyson, and himself that felt pagan, charged with unpredictable energy.

This new arrangement, with each character stalking or receding from the character to their right, some bound by family blood, others the rotten spilled blood of revenge, of bloodlust, of sexual lust, of a heady, self-indulgent nihilism, really sparked life that the franchise has been utterly devoid of. It gave Allyson purpose and actually made her character interesting. It revealed that the Laurie/Michael dynamic alone was getting close to played out. It achieved the perfect balance between too many characters/storylines (Halloween Kills) and not enough going on (Halloween 2019). Rejected by society for committing the ultimate sin, killing a child, Corey is alone in his innocence, and when Laurie fails to kill the boogeymen she lured back to Haddonfield, he becomes not only an outcast but a scapegoat. Driven into isolation his soul begins to fester. And who should lure him out but Laurie, touched by the same darkness, shunned and pursued by death. After saving him from bullies at a gas station (she bandages up his oozing wound, one that looks like stigmata, okay lol a little much), she proceeds to deliver him into the arms of her granddaughter. Laurie unconsciously repeats the trauma inflicted on her when she was Allyson’s age, all but ensuring her granddaughter will grow old with the same oozing psychosexual wound at the center of her being. It’s not that watching her mother die wasn’t enough, it’s that it wasn’t the right trauma, it didn’t have the erotic edge that being pursued forever by a massive, quavering knife has. Of loving someone who wants to kill you: one of the eternal feminine states. If Michael delivers trauma, Laurie is now its handmaiden. Of course she’d be unable to kill herself, but totally able to surrender herself to Michael’s fatal grip.

Laurie fears Corey, but she created him as much as Michael did. And who created Michael? His family? Haddonfield? As for Allyson, there is ripe sequel potential to explore what is bound to develop into an inextinguishable craving for self-harm — not literally, but psychically, sexually, and of course unknowingly. I have seen people complaining about the implausibility of Allyson falling for Corey as quickly as she did, and questioning the logic of their meeting. But to me it seems the most natural thing in the world. Halloween Ends is not quite governed by the unconscious, but unconscious sexual forces and psychological pathologies bend it this way and that like the moon does the tides. Everything on its surface is pretty dumb, but somehow, deep below, David Gordon Green has recovered the machinery that drove the slasher in its purest iterations. It’s sputtering, charging recklessly forward, and he can’t quite control it, but can anyone? Isn’t that the only way we’d be able to recognize it?