This piece was originally published in December 2019

There is a film that premiered this month, the last month of the decade, called Knives and Skin. Directed by Jennifer Reeder, the film depicts the surreal transformation a community undergoes when one of its own, a teenage girl named Carolyn Harper, goes missing and later shows up dead. Knives and Skin may in fact be this decade’s last work of art to employ a narrative device come lately to be known as the “dead girl trope.” This term refers to the use in story of this conceit—a beautiful, young, presumably innocent, usually white girl has gone missing or wound up dead (almost always murdered), plunging the incredulous family/community/town surrounding her into chaos and calling a charismatic detective to chase after answers.

Much lately has been made of the dead girl trope—researching its origins, examining its variations, interrogating its largely uncontested whiteness and cisness. Of course stories of dead and missing women have been around as long as women have died and gone missing, but since the early ‘90s the trope has clogged up the culture, and even moreso in the past decade. Every day we are inundated with stories of women battered, disappeared, manipulated, and killed. We cannot afford to be flip or numb, to treat these stories as just that—fiction, as anything separate from the culture they have a mutually parasitic relationship with. The most important question people have begun to ask of the dead girl trope is whether it has any capacity to attack the misogyny it depicts and uproot the racism and transphobia which support it. Or does recycling the trope again and again, even by creators with the most altruistic intentions, do anything other than entrench the idea that violence is the logical conclusion to the question of a woman?

As the final installment in a decade long saga of women on the verge, how does Knives and Skin measure up? To answer this question we have to do two things. We have to understand the real world stakes, and we have to go back to where this bad dream began.

“When this kind of fire starts, it is very hard to put out. The tender boughs of innocence burn first, and the wind rises, and then all goodness is in jeopardy.”

-Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me

As another year comes to pass, bringing another decade to pass, we find ourselves awash in the bodies of dead girls and women, fictional and very much real.

In the world, women are abducted, disappeared, if returned at all returned in bruised condition, mass graves are discovered, long buried reports of abuse are painfully unearthed, and women are killed. In Nigeria, in 2014, 276 schoolgirls abducted from the town of Chibok by Boko Haram and driven hundreds of miles into ungoverned territory. Five years on, 112 are still missing. Bereft parents have died waiting for their daughters to be returned. “Even in a hundred years,” one mother told a reporter from Al Jazeera this year, “we will keep believing that our daughters will return home.”

In Canada, after years of fierce organizing from within indigenous communities, the government finally launched an inquiry into the murder and disappearance of thousands of indigenous women stretching back decades. The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, as it’s called, attribute it to "state actions and inactions rooted in colonialism and colonial ideologies.” Indigenous leaders name it: genocide.

In our own country, thousands of immigrant women are detained, many having fled their homes due to domestic violence, state-sponsored sexual violence and femicide only to wind up in dehumanizing internment, their children confiscated from them like personal effects. A rising number of mass shooters explicitly name the hatred of women as a call to action, their patterns of domestic abuse (86% of the 22 mass shooters analyzed in a recent Mother Jones report had demonstrable records) shored up too late. Trans women and gender non-conforming afab (assigned female at birth) people face an epidemic of transphobic, misogynistic, often racist violence from intimate partners and total strangers alike. Violence in the street is entrenched by the indifference of the state—of the 22 trans women murdered this year to date, 18 cases remain unsolved.

In the culture, the flood of women’s bodies rises from our ankles to our thighs. Scanning best of the decade lists—it’s easy to see if you’re looking, and even if you’re not, it’s hard to ignore—dead and missing girls are everywhere. Though the carnage is not distributed evenly across formats—there is for example a remarkable lack of dead girl stories in film when compared with the superabundance in television and podcasts—the sheer volume is staggering.

Podcasting emerged as the most exciting new storytelling medium this decade, transforming from local radio curio to culture-spanning phenomenon attracting big tech money and A-list celebrity buy-in. The medium, built on the backs of stories of dead and missing women, has proven unable to go on without them. The show that kickstarted the podcast revolution was Serial, a solemn journalistic inquiry into the unsolved murder of a teenage girl. Serial set off a true crime boom as much as it set a template for much of the medium. Though few shows have applied the same rigor to their dead, damaged, or missing subjects, none have needed to in order to become wildly popular. Simply put, there is no dead woman that eludes the reach of the podcaster, and without dead women, there would be no podcasts as we know them.

Finally, my god, television. It’s not that a number of the best shows of the decade centered on the story of a dead or missing girl; there were in fact so many they constituted a thematic center for the entire medium this decade—The Killing, The Fall, Broadchurch, Pretty Little Liars, How to Get Away With Murder, Making A Murderer, Top of the Lake, True Detective, The Night Of, and The Jinx, to name some of the heavy hitters.

One more show waded into the morass this decade, and most notably—it was the reason for all this mess in the first place.

David Lynch came back to television after 25 years with Twin Peaks: The Return, a third season to his legendary 1990 television series. By all accounts, those original eight episodes launched the beautiful dead girl craze we’re still in the vicious throes of. The entire Twin Peaks universe—Lynch and Mark Frost’s surprise smash first season, the meandering second season in which ABC rescinded creative control from Lynch because he refused to identify the dead girl in question’s killer, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, Lynch’s controversial 1992 feature prequel which features Laura Palmer, dead girl, as an alive protagonist rather than a silent mystery, the new season, and all the apocryphal literary spinoffs—centers on the beautiful, murdered, porcelain-white body of homecoming queen Laura Palmer, washed up on a riverbank in the pilot episode.

Every piece of writing on the dead girl trope addresses Lynch, if not exclusively, then in a fulsome manner. Alice Bolin, who published a comprehensive book of essays on the trope last year called Dead Girls: Surviving an American Obsession, first engaged with the subject in a 2014 essay on Twin Peaks for the Los Angeles Review of Books. And indeed, nearly every review of Knives and Skin I encountered while researching for this essay references Twin Peaks as an obvious ancestor to Reeder’s film.

Why? The aesthetic comparisons are evident—moody score, weird acting, woodsy small town setting, beautiful missing, and then dead, girl. But the comparison is broader than that. It’s almost compulsory, unavoidable. The impact Twin Peaks had on culture is impossible to understate. But the depth to which the twin images of Laura Palmer’s ghostly, smiling, peroxide and permed homecoming photo and her dead, drowned, blue-faced and plastic-wrapped crime scene photo, which the show flashes to in alternation, have seeped into our core imagining of what women fundamentally are in life and in death has absolutely not been reckoned with.

This Knives and Skin grasps. The film’s Laura Palmer, called Carolyn Harper (Raven Whitley), behaves much in the same way. In her first and only alive scene, she and a boy drive up to the shore of a lake at night. Without knowing anything about the film the first time I watched it, I tensed, anticipating exactly what ended up happening. Carolyn and the boy, Andy (Ty Olwin), walk from the car to the lakeside, silhouetted in the glare of the headlights. Before kissing, the two bicker about Carolyn’s glasses, whether they should stay on or be taken off. Andy says “keep ‘em on, I don’t care.” Carolyn responds: “I do care. I actually don’t want to see what’s about to happen.” The next time anyone in the film sees Carolyn, she’s dead.

If Knives and Skin does anything perfectly it’s this. The Laura Palmers of fiction and the Laura Palmers in fact, all around the world, have fused, like the twin images in Twin Peaks—alive: radiant, dead: serene, and in both cases speechless, compliant. It recalls Maggie Nelson’s question after seeing Hitchcock’s Vertigo: “whether women were somehow always already dead, or, conversely, had somehow not yet begun to exist.”

An avatar of young womanhood as always arcing toward extermination has emerged with a juggernaut’s relentlessness out of the scrum of the past three decades of dead girl TV. The characters in Knives and Skin live in this world. Carolyn Harper knows what happens to Carolyn Harpers. She doesn’t want to see “what’s about to happen” because she’s powerless to prevent it. The tagline of the film, “Have you seen Carolyn Harper?” lands as a joke by the end of the film. Carolyn Harpers are all we ever see.

Knives and Skin doesn’t so much rage with righteous injustice over the unfair and unthinkable death of one young girl as it does turn the palpable, ten-ton heavy despair of unfair and unthinkable death as the condition of young girls back on the viewer. “You guys doing okay,” Carolyn’s mother asks three of her daughters classmates who’ve brought her condolence casseroles. Carolyn’s body has just been discovered. An ice cream cake made for her birthday melts into a pale pool of sludge on the table before her. “Yes,” they say, emotionless. “You lying?” They nod again, “yes.”

Reeder has taken us back to the world of Twin Peaks in a time where dead girls are taken for granted, taken as givens. They still, however, even in this most melancholy meditation, destroy communities and upend lives. I’ve said that Knives and Skin doesn’t rage with injustice over the death of Carolyn Harper. But should it?

The reference point that floated into my head while watching Knives and Skin the first time, that I couldn’t shake the second time was not Twin Peaks, but its much maligned and misunderstood prequel, Fire Walk With Me. Lynch made Fire Walk With Me after Bob Iger and ABC tried to stage manage the surprise success of season 1 by forcing him to reveal Laura’s killer. “‘Who killed Laura Palmer?’ was a question that we did not ever really want to answer,” Lynch later told TV Guide. Season 2, largely without Lynch, was as a result baffling, anticlimactic and sensational in all the wrong places. The show was cancelled less than two years after debuting. Fire Walk With Me was a vengeance quest, Lynch’s intent to bring closure and justice to the story of a Pandora he had never intended to let out of the box.

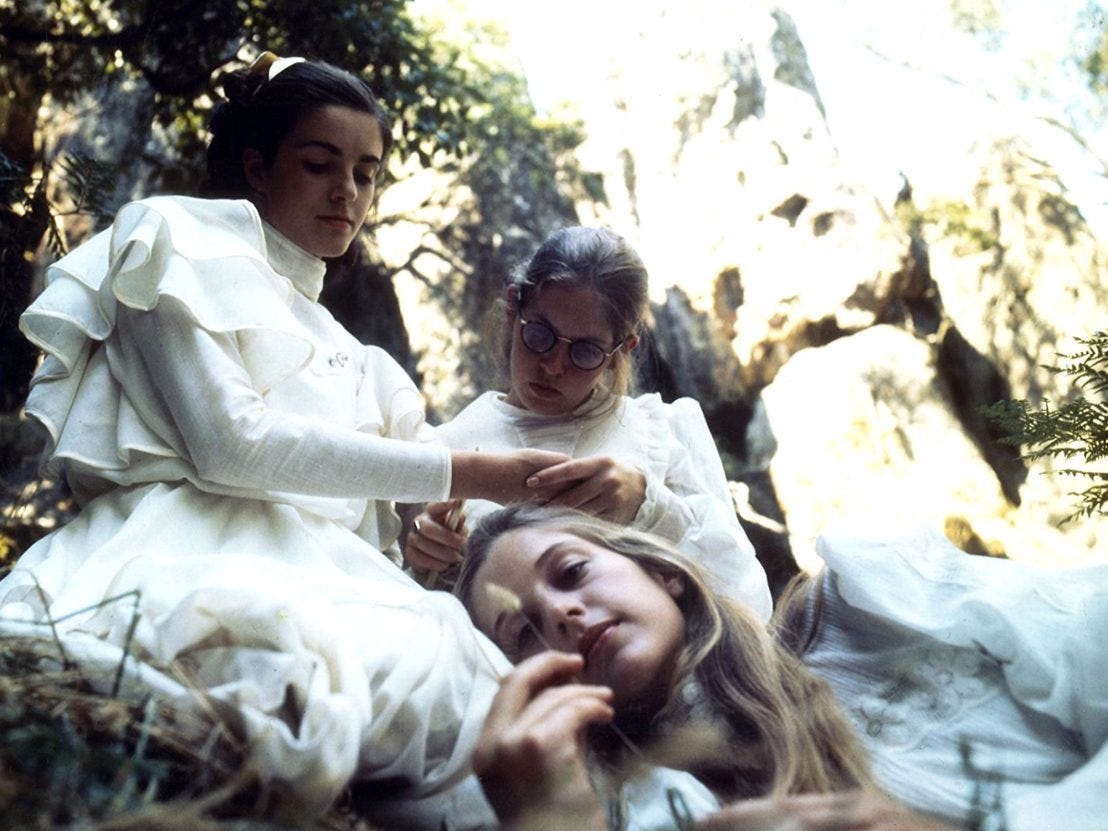

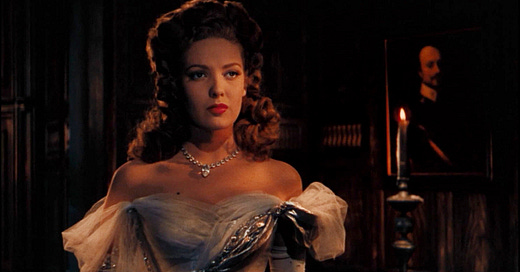

Fire Walk With Me is brutal. Its examination of trauma is surgical, uncompromising, and to the bone. For the majority of the film the camera is glued to Laura, who walks, talks, dances, laughs, gobbles like a turkey, screams, cries, and eventually dies. As a spectator you are shoved in close proximity to Laura. Unlike the silent, pliant Laura Palmer of Twin Peaks, Sheryl Lee’s Laura in Fire Walk With Me is fully alive, every fantasy concocted about her by the characters in season 1 as well as the fans in the audience is in sharp, contested relief. She feels everything done to her immediately, unbearably, and so do you.

Many critics hated Fire Walk With Me, and it was a commercial flop. The film was booed at Cannes. In the New York Times, Vincent Canby wrote: “Everything about David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is a deception. It’s not the worst movie ever made; it just seems to be.” In a discussion on the dead girl trope for The New Republic, Sarah Marshall offered a remark that speaks directly to the film’s icy reception: “a dead woman is utterly incapable of offering up even the most cursory contradiction to the narratives that entomb her as readily as any casket.” Fire Walk With Me was one huge, bleeding contradiction.

The original bad dream, the dead girl’s nightmare we still haven’t woken up from was actually unpacked all those years ago, just months after it all began. Laura’s killer was her father, Leland. Her father had been sexually abusing her since she was a child, her mother knew, and within hours of Laura finally perceiving this fact in its full reality, he killed her. All of the weirdness, the quirkiness, and horror of Twin Peaks, along with the enduring, eroticized, and profitable trope it popularized emanates from this very personal, achingly common story of childhood sexual abuse. Is it any wonder people hated it? Or why the Laura Palmer of the original series is the figure we’ve chosen to preserve, pressed flat into the pages of culture forever?

“All goodness is in jeopardy,” the Log Lady warns Laura before entering the roadhouse where her life will begin to tailspin before its eventual crash. This is the essence and the power of the dead girl story. Though we have erected a world that is impossible for women to navigate unscathed, we continue to vest them with the symbolic responsibility of innocence. As if Laura’s singular life was the first domino in a chain that led to the unraveling of the entire world. But wasn’t it?

Many have pointed out the racial and gender-specific freighting of the dead girl trope. Could Laura Palmer have been Latinx? How would the movie change if Carolyn Harper had been African-American, or trans? The answer on every level, symbolic and real, is drastically. What these depictions unconsciously reflect is the priceless value of white life. Imagine an entire town shutting down operations to mourn and search for a missing black trans woman? We can’t, because when trans women are murdered the only efforts to organize and demonstrations of rage come from within queer communities, often queer communities of color, who have historically adverse relationships with law enforcement. Black women face an escalated threat of violence due to the interlocking forces of white supremacy and misogyny. Yet the disappearance and death of black women and other women of color have historically never been met with the same uproar as with white women who meet the same ends.

It’s not that Knives and Skin is a failure because it seems more interested in the aesthetic allure of a dead girl than in drumming up indignation for the circumstances that configured her death. And it’s not that Twin Peaks was a failure because it prioritized white and cis tragedy over all others. Both Reeder and Lynch have done something profound when it comes to thinking and feeling through trauma, sexual violence, and grief. What remains important is to ask is whether each successive appearance of the dead girl trope is amounting to something, not on the individual but on the collective level. As Bolin has written, “It becomes harder and harder to subvert something that’s been used so many times.”

Have we seemed to make much progress from Fire Walk With Me to Knives and Skin? Honestly, no. But have the horrors real world misogynistic, racist, transphobic violence ceased? Even if rates of violent crime are in fact down in the United States, one disappearance or death like the kinds depicted in Lynch and Reeder’s work would be too many. The most successful iterations of the dead girl trope have grappled with these tough, interceding concerns, like race—consider Top of the Lake and The Night Of. The least successful amount merely to prodding a dead woman’s body with a stick just to see how it feels—consider every episode of My Favorite Murder. The most that I can hope is that future creators considering employing the dead girl trope take the long view of all that came before and ask, is it worth it? Does the dead girl in my story deserve this? What kind of justice, in fact, does she deserve?